Welcome to another installment of the Firm of Her Own series for a unique look at becoming a female architect in New York City. Today we celebrate the impact of women in architecture with the story of AMI Mastermind alumnus, South Africa native Heather Faulding. Principal of her eponymous architectural design firm in Manhattan, Heather is not only renowned for her design work in residential, hospitality, and retail environments but also for furniture, jewelry, and lighting—including a custom chandelier she created for South African President Nelson Mandela (which was purchased by a major celebrity).

Her Perspective: From Fashion Design to Architecture & Creating a Custom Chandelier for Nelson Mandela

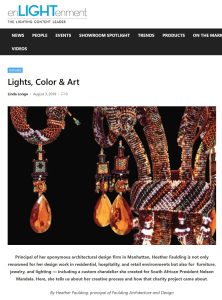

Chandelier for Nelson Mandela, designed by Heather Faulding.

At Architect Marketing Institute, we provide the tools to move from where you are now to Sunshine Island (a place imagined by AMI co-founder and coach Richard Petrie in his story The Village of Archville). We celebrate the way Heather takes action and gets results; ideal clients and dream projects now land on her doorstep! Heather, here, uses those tools wisely. Let’s explore her backstory and philosophy on the way to the paradise where every designer can find success.

What's special about the time and place where you grew up?

I grew up in South Africa in the 1960s, a truly magical climate and horticulture, not to mention school trips and vacations in the bush with animals aplenty.

South Africa has always been a really special place for art, especially the creativity of making art out of whatever is available. Hence the little sculptures were made with leftover telephone wire and later with soda cans and, of course, beads. I was always curious about how things were put together and, to this day, truly love the actual making of things. At 13, I started a dress designing course after school, learned patternmaking, got a diploma, and designed and made clothes for men and women. And then I started leather work and made sandals and handbags with mixed media.

A national high school for the arts opened in my last years of high school; I was thrilled that I was accepted to attend.

What were some of the obstacles or challenges on the way from Johannesburg to becoming a female architect in New York City?

Portraits for the memory of all 8 beloved cats support the bar in steel. Westchester, New York. Project by architect Heather Faulding.

As a teenager, the reality of apartheid, inequality and sexism dulled the euphoria, and 3/4 of the way through my architecture degree I came to the US. Initially, I came to apprentice for a couple of months with Skidmore who was partnered with the firm I was working for in Johannesburg. But I was offered a scholarship to attend university, do a master's, and teach in Indiana. I was and am the only member of my family who came to the US. My parents were British and any immediate family went to the UK.

At the time when I came in 1978, there were very few women in the field of architecture. We were relegated to the decorating and not taken seriously. As I was often told, and it was quite true, being on site we would not be taken seriously.

America was the most likely place for me to do more than select colors, although still tough to break through. [On the journey of becoming a female architect in New York City], I still had very enlightened potential clients ask me all the time who would be doing site work, etc. On-site is where you learn the most when starting out, and in my opinion one of the most important places to be sure that all is being built correctly (no shortcuts or incorrect assumptions or miscommunications between trades that cannot be undone). And I love to learn from tradespeople how they prefer to do things, and then expand this into wider realms with technology as it advances—now often teaching them a little as we go.

What was your path in college & architecture school and what led you there?

Palace Skateboards Los Angeles: A homage to the ancient world, the design includes a curved screen, a dome with video mapping from a stone central “fountain” and mosaics depicting skateboarders and logos. Fountains and friezes with a sense of humor abound throughout, along with a temple entry and an LA-pink awning and entryway. Credits: architect Heather Faulding, photographer Andrew Matusik.

There was no school for fashion design in South Africa. One worked through factories to be able to do this. The industrial design department had a course at the local technical college where I had shifted gears. At the art school, there were no industrial design or “crafts” courses, and I realized that what I loved the most was sculpture and geometrical drawing. One thing led to another and I became passionate about architecture. The universities in South Africa had a very low acceptance rate and required exceptionally high grades in science and math. Women made up 10%, at most, of those accepted. Miraculously, I got in. The school introduced us to broader thinking, which was great; however in the British system, we went to the engineers for land surveying and structure, the math department, and the building sciences section for each subject—rigorous courses in their own right and if you failed more than one, you repeated the entire year. For some, this was several times.

The incredible disdain for the women had 4 out of the 8 women leave after the first year. I had some shocking experiences with professors and more often than not was encouraged to “leave it to the men.”

When I came to the US, most of the courses were taught by and with architects who are much more able to express what we need and there was almost no prejudice of the women attending. (Although I think most of these did not continue within the field for long after.)

Tell me about starting your professional journey and starting your firm—why, to what purpose?

Statues at the Daily Paper Clothing Store. Architecture by Heather Faulding.

I arrived in New York in 1980 in the midst of a recession. I joined a small firm and earned $11,000 a year. To be sponsored to stay in the US, I truly paid my dues for three more years and then joined a large firm where I traveled and ran some international projects, finally happily becoming a senior associate in a large multidisciplinary firm.

I loved the company, the clients, and the work but had climbed into such a senior position that I was managing larger projects and further away from the design and detail of the projects than I wanted to be. So when one of the clients singled me out to do a project for them, I jumped ship and started my own firm, [a Firm of My Own, a milestone in becoming a female architect in New York City where I'd continue to contribute a distinct style through a variety of designs.]

What is your personal mission?

Design by architect Heather Faulding of flagship location for Daily Paper Clothing Store. Photography by Andrew Matusik.

I want to be able to use my immense wealth of experience in new and innovative ways. To be able to draw out our client's souls through design with as much creative expression as possible.

I want to continue using waste materials creatively.

I want to continue to learn, create, and use new technology.

And, of course, to continue to have more exciting clients.

Right now I also have two collections, lighting and separate outdoor furniture that I want to start in a large way. Both of these are recycling materials and hopefully using international refugee labor to assemble parts.

A creative example of recycling materials, pictured here is the Daily Paper Clothing Store in the US. Three Founders of African heritage designed a brand to reflect “Pan-African pride and community.” The store design blends their Dutch base with the inventive ways of African design with recycling and found materials. The beadwork design on the facade was made with soda cans cut and folded by communities that the architect and contractor sponsored to help. The interior had a hidden stair so a glass floor and skylight above the second floor draw the eye and experience to this upper floor.

What are the highlights of your/your firm’s accomplishments?

Waterfront house in the Hamptons with views of the bay and out to sea encapsulated in views at windows in undulating roof lines. Reusing the very nature of classic shingles and trim with an organic and fresh contemporary point of view. Design by architect Heather Faulding.

Highlights include the innovative ways that we have solved problems and stamped each client's individualized signature into each design as well as the incredible range of projects that we have done. We have reworked hospitals and schools, designed housing projects, rebranded and designed stores and restaurants and made many nests for people to live in. I love learning, working with our clients, and building a team. And I love creating the details, which are always different.

Among broader accomplishments, we always challenge ourselves. I love what we can do technologically now, energy-wise, and design-wise, and the recycling and awareness of what we are using and wasting. (There is however much to learn about the wasting.) And I love what we can do with lighting.

Is there a ‘feel’ that is common to all your built designs?

Southampton House bedroom designed by architect Heather Faulding.

There is an individual stamp of the client in each design; we have always transformed space to capture maximum use, light, and context. I think our work is always “happy” or serene, very “clean,” seldom using “dirty” or “sad” colors or dingy leftover spaces unless specifically called for. We custom design for our clients and their sites; we go from the inside out, almost always doing what they had not thought of because we understand their aspirations [and take them further]. We have done highly classical work, remarkably contemporary work, and everything in between.

How has being a female architect impacted your professional relationships and your life as a whole? What was it like becoming a female architect in New York City?

Coffered media room with playful reupholstery of the owner's classic furniture, designed by architect Heather Faulding.

It is so thrilling to see the opportunities and ability to practice as an architect today.

There is absolutely no doubt that we as women bring a completely different perspective to design and architecture. I think we are much more emotionally involved with the use and feel of space and the appearance of structure.

And I don't mean in any soft fluffy way; we just instinctively understand our clients and users differently. We still overdo and overwork the details beyond clients' expectations to our financial detriment. I also think that now that I am older and have so many years of experience and confidence, I care less about others' opinions; as a result, tradespeople understand and respect my knowledge far more quickly than when I was younger. In general, architects, whatever our background and sex, come into our own after many years of experience.

When do you choose to use certain labels? When do you choose to omit them? Why?

New York City Maisonette. Photography: Andrew Matusik. Design: Architect Heather Faulding.

Labels are important for maintenance and longevity where they are going to be installed—lighting and plumbing being two of these. But for me, great design does not need a label. Steve Jobs never allowed his products to leave without performance and design perfection; I believe that even without a label they would stand out. I would always hope our work is the same. And I am most proud to go back after many years to see our work timeless and in great shape.

Pictured: New York City Maisonette on Park Avenue designed to reproduce the classic bones with contemporary detailing and design. A former doctor's office and storage space evolved into a luxurious and highly detailed 4 bedroom apartment opening on to Park Avenue.

If we fast forward to age 100, what do you want to be known for in your work?

Media room design by Heather Faulding.

I want our work to have brought great pleasure and memories, to be timeless and thoughtful design. And personally, the only thing that I care about is being remembered as kind.

Pictured:

Media room with a “hidden surprise” full bar. Sliding resin walls and zebrano wood grain cabinets. Toronto, Canada. Architect: Heather Faulding.

Getting published in leading lighting magazine with the guidance of AMI's Content Team

When Heather participated in the beginnings of the Architect Marketing Institute's Mastermind program, our content team successfully pitched her work to enLIGHTenment magazine, which is “the lighting content leader.” This piece titled “Lights, Color & Art” was written with the guidance of our brilliant writer and editor working closely with the top-tier architects in the program. Thanks to AMI, Heather is now positioning herself as a leader in the eyes of excellent clients with projects in her ideal niches.

Want an inside look at our content team's pitching process? Here are 4 Ways to Amplify Your Content: How to Pitch a Design Project to Publications

Like this story of becoming a female architect in New York City? Listen to this interview with AMI Mastermind alumnus Ritu Saheb on her journey from Mumbai to NYC. Watch architect Mona Quinn's marketing case study here and our co-founder's reflections on this 10+ year success story here.